As I have already mentioned in another article, the composers metronome indications need to be evaluated alongside the descriptive indications of tempi given in the score, and with regard to realistic possibilities of technique. The pulse of mm=76 for the first movement is hugely ambitious as regards technique, and possibly erroneous when it comes to interpretation, as we are presented with an opening Sostenuto in 3/4 and 5/8 followed by a compound signature of 14/16 (7+7/16) marked Allegro ma non troppo, plus a coda where the metronome mark is equivalent once again to each crotchet. Whatever tempo is actually chosen by the pianist it is at least clear that the tempo relationship between these three parts should be equal and constant.

How I have arrived at a suitable approach to these tempi for my own recording is discussed below.

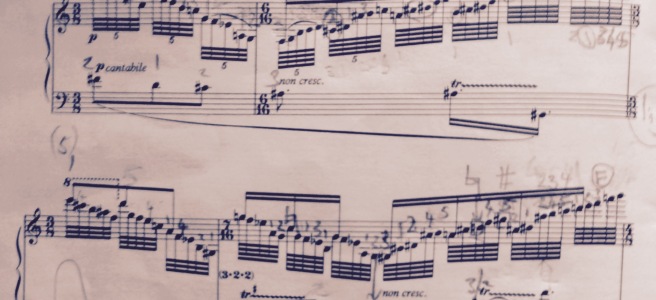

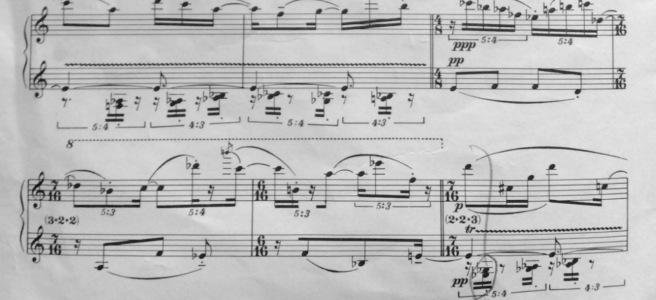

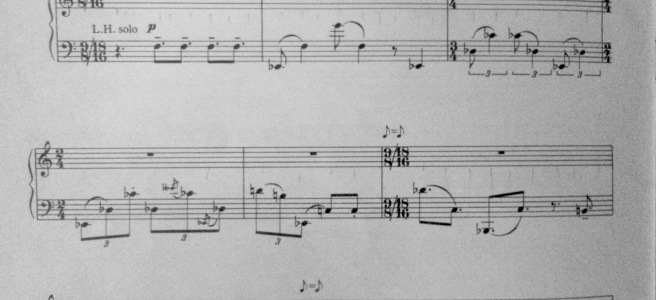

The opening Sostenuto comprises ten bars which contain not only the essential tonal and modal material of the first movement but also, as one might expect in the twentieth century, for the whole Sonata. Previous interpreters have tended to slow down this short opening section [bar 1-10] considerably, to give it due weight as a praeludium perhaps, and to indulge the legato phrasing in a poetic way at the low dynamic. The contrast thereafter from bar 11 in the movement could hardly be greater, where stillness and transparent texture is suddenly replaced by a dense and feverish polyphony, syncopated between the bass line elaboration and a counter melody played as clashing major sevenths in the right hand. All this is brazenly ornamented with abrupt tone clusters and grace notes, which gradually serve to increase the hesitation before the compound beats of the 14/16 bar (like musical glottlestops) which gradually becoming more extended and more intrusive.

The effect at the forte dynamic (easily becoming a fortissimo aggregate in various recordings), can be very unsatisfactory if the listener merely is taken aback by a wild and unannounced energy after the quiet opening, assaulted by a challenging overload of material and containing so many accented notes that the tempo itself is not able to be felt as intended. Undoubtedly the intention of the argument starts with little compromise, but I recall in so much of the composers orchestral writing the separate timbres that are used to keep musical lines from colliding, so every effort must be made by the pianist to play trills and scale/flourishes with luminous tone and at a lower dynamic than the rhythmic melodies.

I have endeavoured to keep the tempo clear, and the same as the crotchets of the opening, with a tempo about 59 which certainly feels fast enough, but allows for the lightness of touch that helps all the textures shine. During the 14/16 main passages, the only notes requiring the forte dynamic are those indicated as accented in the lower part of the right hand countermelody, and more so, those initial notes of the left hand in each bar with their own accent marks.

Even a tempo of 59 (rather than the 76 indicated in the score) might feel a considerable amount faster than “Allegro ma non troppo” but I feel the composers indication is based upon the two even and swaying compound beats of the bar, particularly when considering the left hand alone. If this underlying pulse is appreciated by the listener then a more successful interpretation should be possible.

To be continued…

l

l

David Holzman, Centaur CRC 2102 (1993)

David Holzman, Centaur CRC 2102 (1993)